No Other

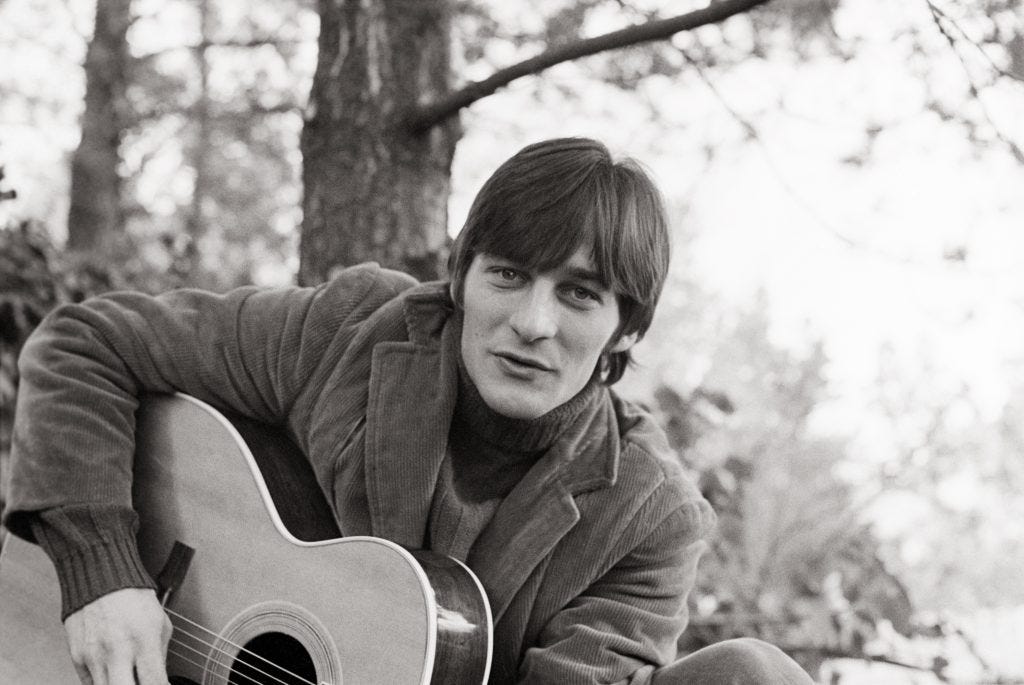

Gene Clark on a sweltering Auckland afternoon

Quentin Tarantino rivals only Martin Scorsese as a master of the needle-drop soundtrack. In his debut film Reservoir Dogs, the song choices even came with their own wrap-around conceit: a fictional radio station, “K-Billy’s Super Sounds of the Seventies,” hosted by comedian Steven Wright playing a DJ so flat as to border on nihilism. I imagine months of listening and discovery for both directors, searching every nook and cranny for music that both entertains and collectively settles the film’s overall tone.

Their attention to detail is also a flex. Tarantino, especially, uses his music choices to expose how idle his peers can be. The clearest example is in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, a film that mere artisans would have stuffed full of Hendrix and The Doors - maybe Eric Burdon and the Animals if they were feeling perky - retro shorthand instead of the popular music people were actually hearing on their car radio at the time: Paul Revere & the Raiders and assorted bubble-gum acts.

Also frequently missing from conversations about the 1960s music scene is country and country-rock. Even many of the folk acts of the era were country by another name. The Grateful Dead. Country Joe and the Fish. Buffalo Springfield. The Byrds. It would be their offspring (and solo acts from some of the above-mentioned bands) who ruled the seventies with stadium-filling success: Delaney and Bonnie, The Band, The Eagles, John Denver, Glen Campbell, and Linda Ronstadt. Eric Clapton and The Rolling Stones quickly abandoned psychedelic silliness for Americana, the latter gifting the world Exile on Main Street, while Leon Russell was second only to Led Zeppelin as an arena-packer in 1972.

I was lazing with a lover the other day when Polly by Dillard & Clark rose out of a playlist like steam off a glistening vaginal mound. The duo, short-lived but highly influential, paired banjo virtuoso Doug Dillard with Gene Clark, a founding member of The Byrds and writer of “Eight Miles High.” Clark was - it is more than fair to say - a gorgeous man - more striking than Jim Morrison - with dark hair and high cheekbones betraying some Native American heritage. For a time, he was unofficially The Byrds’ frontman, until internal squabbling over royalties and health issues saw him depart at the height of the band’s fame.

Clark would never be this famous again, despite releasing some incredibly haunting work that, sold right, might have made him country’s Leonard Cohen. Instead, he died at 46 in 1991 from a bleeding ulcer, the result of decades of heroin addiction and heavy drinking.

I am a fan. Especially of Clark’s broken instrument. His soul. Cohen never sounded particularly troubled to me. Jewish and intellectual, you never got the sense he was short of a bedfellow whom he’d welcome with delight and maybe even an element of surprise. This tempers the melancholy Cohen aims for. Clark isn’t aiming for anything. He is the bullseye missiles hit. And this tells you a lot about why we need music, or art generally: to spend time with the unhappy: to find clues as to how to evade our own myriad prisons from those who were unable to escape. Another way to put it is we can only rise from the depths.

Gene Clark was born Harold Eugene Clark, the third of thirteen children, on November 17, 1944, in the small railway town of Tipton, Missouri. The Clark family later relocated to Kansas City, which wasn’t just jazz territory - it was saturated with country, gospel, and revivalist Christianity. Clark grew up in a devout Protestant environment, often described by contemporaries as Pentecostal or Church of God–leaning in temperament, if not always formally denominational. Church music was central: four-part harmony, call-and-response singing, minor-key laments.

By eleven, he was playing guitar. By his teens, he’d absorbed The Everly Brothers, Hank Williams, The Louvin Brothers, and early rock ’n’ roll. His singing was never decorative - it was functional, communal, earnest. You believed him, which beats a trained voice box any day of the week.

After a professional start in Kansas City, Clark moved to Los Angeles in 1963, chasing something larger but undefined. He briefly associated with folk groups and is often reported to have auditioned for - or at least orbited - the New Christy Minstrels, a key incubator for folk professionals of the era. Whether formal or fleeting, the point stands: Clark was already circling the machinery of the folk revival before The Byrds.

In L.A., Clark crossed paths with Roger McGuinn and David Crosby, who were experimenting with electrified folk under names like The Jet Set. McGuinn had technique; Crosby had bravado. What they lacked were songs that sounded finished. Clark supplied those.

On the first two Byrds albums, Clark sang more lead than anyone else. Early publicity photos placed him front and centre. For a brief window, he was the band’s emotional axis.

The Byrds, as history flattens them, are remembered as Dylan-electric pioneers. What they actually represented – due to Clark - was the fusion of British pop intelligence with American country fatalism: post-romance autopsies. The Rickenbacker jangle gets remembered; the Missouri ache does not, perhaps due to Clark’s departure.

His collapse inside The Byrds wasn’t only over money. It was neurological. Clark suffered from severe anxiety, particularly a fear of flying, which made national touring unbearable just as the band exploded.

So, in 1966, with the band now an international success, Clark left - or rather, withdrew. The pattern was set: create the thing, then be forced to retreat from its consequences, either inside a bottle or a syringe.

There was more work. The Fantastic Expedition of Dillard & Clark (1968) is now recognised as a cornerstone of country rock, but at the time it was commercially awkward - too rural for rock, too strange for Nashville.

Their version of the Beatles’ Don’t Let Me Down feels like the philosophical heart of Clark’s career. Lennon’s original is public desperation - athletic, sweaty. Clark’s interpretation is private resignation. He sings it like someone who already expects disappointment and is managing expectations accordingly. The country rendering is so apt you’d swear the Beatles were covering Dillard & Clark. Sneaky Pete Kleinow’s pedal steel - he of the Flying Burrito Brothers fame, later lending his jazz-inflected phrasing to Joni Mitchell, Jackson Browne, and Lennon himself - seals it.

Dillard & Clark feels like a hinge moment in country music. You can hear their influence right through to the Grammy-winning work of Robert Plant and Alison Krauss, who covered Clark’s ethereal Polly.

And this was the song that drifted over two naked bodies on a wet, sweltering afternoon yesterday, rearranging the furniture in my chest. It’s almost post-sad and could easily have been slathered with cinematic strings à la Lee Hazlewood - but it resists that. It resists everything. Just a dry, woody guitar, close-mic’d, and Clark’s faintly tremulous longing. A letter never sent.

On a podcast I heard a year or two back, Michelle Phillips of the Mamas and the Papas confessed to having taken Clark as her lover. She called him “Beautiful. One of the most beautiful men.” He was that. But, as she would acknowledge, crippled inside.

As often happens, alcohol becomes a medicine of choice for the anxious - the only surefire solution to some ailments, especially those of the mind - while quietly killing the body. I, myself, am ten years sober, but I found that drinking eased my mild Tourettes. Crosby – no stranger to abuse - became a household name through Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, earning a Dennis Hopper-esque sixties-survivor mantle that turned him into a cuddly nostalgia act as likely to wander onto Roseanne, The Howard Stern Show, or voice The Simpsons as produce any new music.

Clark produced a cult album, No Other, that bombed on release but is admired in unexpected quarters now, and lived perpetually short of money, relying often on the goodwill of friends, though he did reunite with The Byrds for their induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. But his body was breaking down at this point. I’ve seen a body broken down by alcohol. It is one of the saddest songs ever sung.

For soaring, emotional roots music, I’ll take the earnest, terminally wounded Clark over the clever-pants harmonising of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. Clark is another artist who proves that pain can be the most affecting instrument – and will always be worth more than a thousand Steinways.