כָּל הַמְאַבֵּד נֶפֶשׁ אַחַת… כְּאִלּוּ אִבֵּד עוֹלָם מָלֵא

Saying Goodbye to Playwright Stanley Makuwe

Whoever destroys a single soul… it is as though they destroyed a full world.

I met Zimbabwean-Kiwi playwright Stanley Makuwe in 2010. Our first meeting was on K’rd while it was still relatively hip, but already – regrettably - cleaning up its act. I worked on the second floor of a crumbling old building, producing documentaries and winning my boss big tenders. We were hunting for subjects for a proposed documentary series called Minority Voices to screen on TVOne - a first-of-its-kind that would present intimate portraits of new migrants to Aotearoa, still carrying the psychic luggage of other countries. Arab. Asian. South Asian. Eastern European. And African.

Despite a very clear brief for personal stories, the many Africans we interviewed for the show treated me as if I were Simon Cowell. I saw dancers, jugglers for christssake, and had to break a lot of hearts by telling them this was to be a character-driven documentary, not a talent quest. We eventually found our people, and Stanley was one of them.

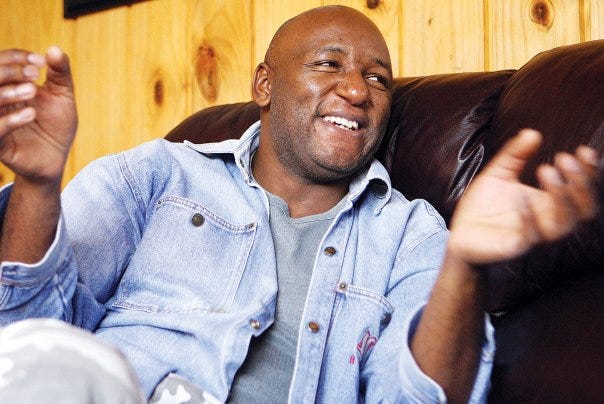

Stanley was a big guy. Taller than my own 6’2”, built like a lock-forward, head shaved and the colour of dark Equatorial chocolate, and while not out of shape, there was a strange boneless quality about him in his long arms and the lope when he walked.

I had had a mildly bruised history in professional theatre, and recognised Stanley immediately as one of my people. I felt an almost proprietary urge to help him, to back him, to make sure this big, brilliant man didn’t get quietly lost in the cultural shrubbery.

Around this time, he was remounting a play called His Excellency Is in Love, a ferocious satire about a Mugabe-esque despot who tips from revolutionary heroism into full-blown autocratic insanity after marrying a much younger woman. The play did appear to apportion the majority of blame at the young temptress’s feet. Stanley told me that back in Zimbabwe, the authorities had shuttered the theatre on opening night, just as the curtain was about to rise. Some states take being made a punchline as seriously as a suspicious package under the President’s car.

I attended a rehearsal and remember being swept up in the raw voltage of it. Stanley had pulled together a genuinely pan-African ensemble, actors from across the continent, many French-speaking Congolese, and one deeply traumatised Rwandan whose history sat in the room with us like a second script. I would go on to shoot his story too in an episode full of horrors unsuited for its Saturday at 10:30 am timeslot, such as his playing dead among real corpses to survive a genocide. Trauma was always ringing in the ears of this young man, who had already completed a prison term in New Zealand before I met him.

Spending time with the cast over a research period, and the week I shot with them, I was able to get a sense of the diversity of the continent. I certainly had an affinity with the French speakers, but Stanley was brought up in a school system pretty much like our own. We became tight. Once the man, always the man, he would say to me.

The woman cast as the young wife was an Ethiopian actress, so striking she seemed almost unreal to me. The others in the cast could see I was captivated and mocked me for it. I could’ve happily let her ruin my life. The play itself was loud, coarse, absurd, and deliberately excessive. Power mocked until it squealed. The energy crackled. This was a farcical style so effective in reducing those in power, but one that we never really explore in our buttoned-down theatrical culture.

One afternoon, Stanley and the Rwandan marched into my production office to announce that they had just experienced racism. A shopkeeper, they said, had refused to sell them a hat required for the production. They wanted me to confront the man on their behalf.

I returned with them to the shop. It turned out the hat was a display model, clearly labelled not for sale. No racism. Just a misunderstanding. Everyone laughed, eventually. What stayed with me wasn’t the mistake, but the readiness to draw a certain conclusion. I can relate to this. If you’re used to getting hammered for you are, you can brace for impact even when the road is clear.

Life, as it does, pulled us onto adjacent but diverging tracks. I left documentary and drifted deeper into comedy and film. Stanley kept grinding away in the theatre. When I later saw his name attached to the Auckland Theatre Company, I felt an unearned but real sense of pride. Good, I thought. He’s on his way.

Many would come to know him best through Black Lover, which premiered in 2020, a play about Sir Garfield Todd, the New Zealand-born Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia, deposed and placed under house arrest as a race traitor. The production was sharp, humane, beautifully acted, and it sold out. COVID cut its legs out mid-stride (I think we all have that story), but it returned later that year. Audiences came to Stanley’s play. Critics paid attention. Stanley’s voice was no longer on the margins.

By day, Stanley worked as a psychiatric nurse in mental health. By night, he wrote plays. Relentlessly. Zimbabwe. Aotearoa. Wherever the stories demanded. His final work was brutally intimate: I Am Tungsten, a play about his receiving a terminal diagnosis. Even then, Stanley was transmuting fear into form, illness into language. Writing wasn’t something he did. It was how we writers stay upright.

Stanley adored his son Wendell, whom I first met as a small boy and later followed from afar as he became an amateur championship boxer. Stanley posted photos constantly, pride radiating off the screen. I’m a boxing tragic myself - it would have been an easy bridge back to one another. But I didn’t take it.

I learned of Stanley’s death on Facebook. I hadn’t even known he was ill.

I saw the photographs - some of which I am sharing here - and was hit with a rush of memory: the laughter, the hunger to tell stories, the sheer refusal to be quiet. And my heart cracked open. This death felt truly obscene in its unfairness.

We say in our faith that to take a life is like destroying an entire world. This is where the sages are so clever. On the surface, profound if somewhat inflated. But meditate on it for mere moments, and it reveals a literal truth. The world is experienced by each of us in a very unique way. We each have our own distinct lens on this world that vanishes with our passing. And how much more so the playwright, who furiously creates countless new worlds for all of us to enter and experience? How many worlds has Stanley’s passing stolen from us? And what of the worlds of his family - a wife and three children - which may still exist - but will be experiencing now an ice age - frozen until a distant future thawing when the pain is almost - but never quite - bearable.

Goodnight, friend. I am kicking myself for not reaching out to you.

Sounds like a fascinating man. I regret not having caught productions of his plays. Now doing laser-focus (as Luxon would say) on arts / music / culture articles, ignoring political ones, Enough of them around on other substacks anyway. .